1.Introduction

Buddhism is founded on two fundamental beliefs, from which the rest of the philosophy is derived. These two basic premises are:

(i) The underlying nature of reality is process and change, rather than stable entities.

(ii) Processes can be divided into two categories - mental processes ('nama') and physical/mechanistic processes ('rupa').

Although mental processes and physical processes interact, mental processes are not reducible to physical processes.

1.1 The process nature of reality.

According to Buddhism, the basis of reality consists of ever-changing processes rather than static ‘things’. If any ‘thing’ is analysed in enough depth, and observed over a long enough timescale, it can be seen to be a stage of a dynamic process, rather than a static, stable thing-in-itself.

This becomes obvious when we remember that the universe is itself a process (a continuing expansion from the Big Bang), and so all that it contains are subprocesses of the whole.

1.2 Mechanistic and mental processes

There are two kinds of processes in the world, mechanistic and mental. Mechanistic processes explain the working of all machines including computers, and all the classical laws of science including biology, chemistry, and physics.

Mental processes consist of irreducible aspects of consciousness that have no mechanistic explanation, for example qualia (qualitative experiences such as pleasure and pain) and intentionality or aboutness (the power of minds to be about, to represent, or to stand for, things, properties and states of affairs).

1.3 The Buddhist viewpoint

This introduction to Buddhist philosophy will start by reviewing how process philosophies, such as Buddhism, have long been neglected in the West, but have undergone a recent revival due to the process perspectives of modern science.

I will show how the key Buddhist concepts of impermanence and emptiness are logical consequences of a process view of the world. I will then discuss why mechanistic processes cannot account for such mental phenomena as qualitative experience, and ‘aboutness’ (intentionality). This inadequacy of a purely mechanistic worldview is known as ‘The Explanatory Gap’, or ‘The Hard Problem'.

Finally, I’ll examine how many of our delusions arise from the inability of mechanistic processes to give a true picture of reality, followed by some techniques for liberating the mind and transcending these delusional constraints.

2 Process Philosophy

|

| Everything is process |

For anyone new to Buddhist Philosophy, the main thing to bear in mind is that Buddhism is process philosophy, in contrast to most familiar varieties of Western philosophy which are substantialist philosophies.

Process philosophies hold that the fundamental nature of reality is one of constant change and dynamism, and phenomena that we think of as permanent substances or things, are just snapshots of processes at different stages.

If we observe any seemingly permanent entity in enough detail over a long enough timescale, then we will indeed discover it is a stage of a process or processes. Thus ‘permanent’ features such mountains and hills are stages of processes involving plate tectonics and erosion etc. Even the most fundamental particles are processes rather than things, as they exist as ever-changing wave-functions that only appear as well-defined ‘things’ at the moment of observation.

Substantialist philosophies, in contrast, hold that things and substances, or their ‘essential natures’, are the primary fundamental basis of reality, with processes being secondary phenomena.

Substantialism is strongly linked to the idea of essentialism - that things and substances have an ‘essential nature’ that makes them what they are.

2.1 Neglect of Process Philosophy in the West

Process Philosophy holds that the underlying basis of reality is change, process and impermanence. Becoming is more basic than being, and existence is really just impermanence in slow-motion.

The converse view - Substantialism, holds that true reality is 'timeless' and based on permanent ideal forms. Change is accidental, whereas the substance is essential.

Traditional Western philosophy has always denied any full reality to change, which is conceived as only accidental and not essential.

Substantialism has dominated Western philosophy from the time of Plato until the early twentieth century, and is still deeply embedded within our culture.

There were indeed Process Philosophers among the early Greeks. For example Heraclitus pointed out that no-one can step into the same river twice. It's not the same river nor is it the same person.

Nevertheless, the early process philosophers were ignored or forgotten, and the theory of ideal forms propounded by Plato was adopted by the later Greeks and dominated Western thought until the early twentieth century. As the modern process philosopher Whitehead remarked, most of the western philosophy carried out during the intervening centuries was 'a series of footnotes to Plato'.

2.2 The scientific perspective on Process Philosophy

From the mid nineteenth century to the early twentieth, a series of revolutions took place in science which changed the scientific outlook from substantialist to process-based, and simultaneously demolished the 'essentialist' view of material objects and living things.

2.2.1 How process thinking became dominant in physics and biology

2.2.1.1 Evolution

Until Charles Darwin published The Origin of the Species in 1859, almost everyone believed that species are unchanging and derive their forms by reference to a divine blueprint. Theology had long been dominated by the ideas of Plato, who taught that the species were invariant, deriving their characteristics from reference to 'essences' or 'ideal forms' which were fixed, eternal and inherently existent.

However, Darwin showed that new species are formed by processes of gradual change from simpler forms. All primates (including humans and apes) have a common ancestor. Going back further, all species of mammals diverged from a common ancestor, and so on into the dim and distant past until we reach one common ancestor of all lifeforms, which originated the DNA coding which is universal for all plants, animals, fungi and bacteria on earth.

Consequently, to evolutionists the biological species concept does not reflect any underlying reality. A species is purely a snapshot of an interbreeding population of organisms at a particular epoch in time, and as time progresses the characteristics of that population will gradually change in response to selective pressures. The process of evolution is the fundamental basis of all biology, whereas the species of living things are secondary and transient outputs of this process.

2.2.1.2 The non-existent Luminiferous Aether

Just as the theory of evolution emphasised dynamic processes, rather than static species, as the fundamental realities of biology, a similar transformation of thinking was to affect physics a few years later with the negative result of the Michelson–Morley experiment.

Until the nineteenth century, it was believed that all waves must propagate through matter. In other words, processes such as sound and water waves needed some substance to support their existence. It was therefore assumed that space was filled with a 'luminiferous aether' through which electromagnetic waves such as light, heat, radio waves, X-rays etc propagated like ripples on a pond. But the Michelson–Morley experiment demonstrated that this aether did not exist, and thus electromagnetic waves were standalone processes with no supporting substance. Quantum physics was later to show that the fundamental particles of matter are also processes.

Later work has also demonstrated that although empty space doesn't contain any substance such as aether, neither is it completely empty. In fact, it consists of myriads of microscopic processes which are continually producing transient energy fluctuations (see Subtle Impermanence).

2.2.1.3 Quantum Physics

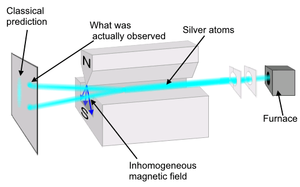

In the early twentieth century, developments in quantum physics revealed that fundamental particles weren't the little irreducible billiard balls of classical physics The particles, which had previously been regarded as little pieces of matter, are instead processes consisting of continuously evolving and changing wavefunctions. These processes only give the appearance of discrete and localized particles at the moment they are observed.

So particles are forever changing, and they lack any inherent existence independent of the act of observation. Consequently, everything composed of particles is also impermanent and continually changing, and no static, stable basis for its existence can be found.

Process-like behavior isn't just confined to fundamental particles such as electrons and protons, but also applies to their combinations. Some surprisingly chunky objects such as bucky balls show formation of an interference pattern when a they pass through a double slit.

2.3 Process and Essentialism

Essentialism is the belief that, for any specific entity (such as an animal, a group of people, a physical object, a substance), there is a defining essence within them that makes those things, groups and substances what they are.

For the best part of two thousand years essentialism held sway over the Western mind, firstly in the form of Platonic essences, then as the unchanging species of the Bible, and finally as nineteenth century atomic substantialism.

Essentialism underpins substantialism, and has no place in process philosophy. Essentialism has been undermined by the same scientific discoveries that undermined substantialism.

2.3.1 Classical physics

The first cracks in the essentialist edifice are apparent, in retrospect, with Newton's discovery of the laws of motion.

Before Newton, the heavenly bodies wandered around the firmament according to their different essential natures as decreed by the 'Unmoved Mover'.

After Newton, the stars, planets, moons, comets and asteroids moved according to the same mathematical relationships.

Before Newton, stars, planets, moons, comets and asteroids were separate entities. After Newton there was a continuity in size and composition from the tiniest 'grain of sand shooting star' through meteorites, asteroids, comets, moons, miniplanets, small planets, gas giants, brown dwarfs and all the different sizes of stars.

Before Newton there was the concept of the 'Unmoved Mover'. After Newton every action had an equal and opposite reaction. As a consequence anything that produced a change was itself changed. Therefore ALL functioning things must be impermanent. These observations were never taken to their logical conclusion by European philosophers in Newton's day, possibly because heresy still attracted severe punishment in most European countries.

2.3.2 Chemistry and Particle Physics

Chemistry provided a bastion for essentialism up to the late nineteenth century. All substances were composed of atoms of about 80 (then) known elements. Every atom of a particular element was identical with another atom of the same element, and derived its properties from the essential nature of that element. The atom was fundamental and unchangeable.

The first hint of atomic substructures came from the work of Mendeleev, who published his periodic table in 1869. He left gaps in his table for as yet undiscovered elements and was able to predict their properties.

Work on radioactivity in the early 20th century demonstrated that atoms were not fundamental but were composed of elementary particles - electrons, protons and neutrons. It was found to be the number of these particles within each atom of an element that determined the properties of that element, not some inherent substantial essence.

In addition, these elementary particles did not act like classical 'things'. They were only knowable by interactions with other particles, and the mere act of observation changed their properties in an indeterminate way.

Even worse, their 'essential nature' seemed to change radically according to how they were observed. If you set up your experiment to observe them as particles, then they behaved as particles. If you set it up to observe them as waves, then they behaved as waves.

2.3.3 Evolution and Genesis

'The Origin of the Species' was the first major blow against essentialism in the West. In 'Darwin's Dangerous Idea' Daniel Dennett writes 'Even today Darwin's overthrow of essentialism has not been completely assimilated .... the Darwinian mutation, which at first seemed to be just a new way of thinking about kinds in biology, can spread to other phenomena and other disciplines, as we shall see. There are persistent problems both inside and outside biology that readily dissolve once we adopt the Darwinian perspective on what makes a thing the sort of thing it is, but the tradition-bound resistance to this idea persists.'

So the full implications of the collapse of essentialism have yet to fully permeate the western psyche. But the radical change in the way that science views the world which took place between 1850 and 1950, has brought western thought far more in line with Buddhist philosophy than at any time in the past 2500 years. This may partly explain the rapidly growing interest in Buddhism among scientifically literate westerners.

2.4 Impermanence and existence

The impermanence of all functioning phenomena is an inevitable logical consequence of their emptiness of inherent existence.

No functioning phenomenon can be static, because to function it must change and be changed, it must give something of itself or receive something into itself. A truly unchanging phenomenon would reside in splendid isolation and could never even be known to exist. All functioning phenomena are composite and impermanent. What we term ‘existence’ is really just impermanence in slow-motion.

2.5 Emptiness

No phenomenon is a ‘thing in itself’. The more you look for it, the less you find it. Things disappear under analysis. A car exists as a conventional truth, convenient for our everyday lives - a kind of working approximation. But on dissection, logical analysis can find no ‘essential’ car, just a heap of parts that at a certain arbitrary stage of assembly is designated ‘car’, and at a certain arbitrary stage of disassembly is designated 'pile of junk'.

Outside our mind there is no defining ‘carness’ . Similarly, if you gradually decrease the height of the sides of a box until it becomes a tray, there is no point at which 'boxiness' leaves and 'trayfullness' jumps into the structure, with the box being automatically transformed into a tray. It’s all arbitrary mental designation. This arbitrariness is the ultimate truth of how things exist to our minds. And it goes all the way down to the fundamental particles of matter.

2.6 The two truths: conventional and ultimate

Although it may be true that all functioning things are processes, it doesn't help us to find our way around the everyday world. Conventionally, we regard any object that exists relatively unchanged for a long enough duration to be useful, as a 'thing' rather than a process.

This is similar to the situation where knowing that matter is 99.9% empty space is of no use whatsoever when we're building a brick wall.

So reification (regarding processes as things) of functioning phenomena is a conventional truth - a working approximation that allows us to function in, and find our way around the world.

In Buddhist ontology process is primary, substance is secondary. So ultimately the entire world that we function in, and find our way around, is itself a process, and will eventually cease to exist. The world and all that's in it lack any enduring identity that has the power to prevent impermanence from sweeping them all away. That is their ultimate truth.

And even the concept of 'existence' is itself a conventional truth. To say that any functioning phenomenon 'exists' is a commonsense approximation to saying that it endures for a relatively long time. 'Existence' is really nothing other than a less blatant form of impermanence.

So both conventional truth and ultimate truth are valid for their respective purposes, in the same way that classical and quantum physics are both valid.

If we want to design and build a bridge, we think in terms of classical physics. If we want to explore the ultimate nature of matter, we think in terms of quantum physics.

Likewise, if we want to build a Dharma center, then we use conventional truths to assemble all the conventionally existing things that are needed - stones, bricks, beams, windows, doors, cables, pipes etc.

If we then want to sit inside the finished Dharma-center and contemplate ultimate truth, we may reflect on how the ultimate truth of the Dharma-center is that it exists dependently upon the causes and conditions that built it, the parts from which it was built, and our mental labelling of it as 'Dharma-center'.

But the more you look for it, the less you find it. If we think that the Dharma-center actually exists from its own side, then we may try to pinpoint the exact stage of its construction at which 'heap of bricks' suddenly ceased to exist and the 'essence of Dharma-center' jumped into the structure to make it the thing that it is.

And of course we'll never find that sudden transformation, because 'essence of Dharma-center' only exists in our own mind, not within the structure of the Dharma-center.

3 Minds and mechanisms

|

| Alan Turing |

"When the body dies, the 'mechanism' of the body holding the spirit is gone, and the spirit finds a new body sooner or later, perhaps immediately."

– Alan Turing on the death of his boyfriend.

There are two kinds of processes in the world, mechanistic and mental.

Mechanistic processes explain the working of all machines including computers, and all the classical laws of science including biology, chemistry, and physics. All mechanistic processes can explained, modelled and simulated by Turing machines.

What Turing referred to as the 'spirit' would be what Buddhists would call the 'mental continuum', a process that knows its objects (generates intentionality) and experiences qualitative states such as aversion and attachment, pleasure and pain.

Thoughts about things, and minds of attachment and aversion (eg an angry mind) arise as subprocesses of this primary mental continuum, and then dissolve back into it, a phenomenon that can be observed in mindfulness meditations.

Mental processes can continue to operate when the mechanism of the brain has shut down.

These mental processes consist of irreducible aspects of consciousness that have no mechanistic explanation, for example neither qualia (qualitative experiences), nor intentionality (the power of minds to be about, to represent, to give meaning or to stand for, things, properties and states of affairs) can be modelled, simulated or explained in terms of a Turing machine or combination of Turing machines.

Mental processes do not appear to be physical, for when we seek to bridge the gap from the processes taking place in the brain to those the mind, we inevitably reach a point where the methods of investigation, explanation and simulation pursued by mechanistic science (in the form of Turing machines) are exhausted, and 'physical' understanding comes to an end. Logical continuity between matter and mind disappears, and we are left in a perplexed contemplation of mysterianism.

This explanatory gap is known as 'The Hard Problem of Consciousness'.

4 Delusions

|

| Are we all deluded? |

There are two kinds of delusions - innate delusions and intellectually formed delusions.

Innate delusions result from our non-physical mental processes being attached to our bio-physical bodily processes, including those of the nervous system and brain, which have been driven by evolution to give us a picture of the world that is merely fit for purpose, rather than one that represents some true underlying reality.

Intellectually-formed delusions consist of pernicious mind viruses, memes and memeplexes such as bogus religions. Another intellectually formed delusion is that of materialism, which is to some extent inspired as a reaction against the excesses of memetic religions.

4.1 Innate delusions

4.1.1 Reification

To reify is usually defined as mistakenly regarding an abstraction as a thing. It is derived from the Latin word res meaning 'thing'.

Reification in Western philosophy means treating an abstract belief or hypothetical construct as if it were a concrete, physical entity. In other words, it is the error of treating as a "real thing" something which is not a real thing, but merely an idea.

In Buddhist philosophy the concept of reification goes further. Reification means treating any functioning phenomenon as if it were a real, permanent 'thing', rather than an impermanent process.

The basic delusion is that we believe that all substances, objects and people have an unchanging, stable, defining nature ‘from their own side’ that makes them what they are. This delusion of intrinsic nature, is known as ‘svabhava’ (Sanskrit for ‘inherent existence’), and can be refuted philosophically by the 'emptiness' argument, and scientifically by recognising the process nature of reality.

Although we may understand intellectually that inherent-existence is impossible, nevertheless we still have great difficulty of ridding ourselves of this delusion. The reason that svabhava is so deep-rooted, pervasive and systematic is that our brains and perceptual systems have evolved to use svabhava as a useful working approximation (or ‘conventional truth’) to represent commonsense reality.

This ‘working approximation’ functions quite well in our everyday life, and only breaks down when we analyse phenomena in depth, either philosophically, or scientifically as with particle physics, where we are forced to realise that the observer is an inextricable part of the system.

4.1.2 Other biologically based delusions

All animals, including ourselves, have genetically programmed drives to eat, reproduce, fight for territory and mates, kill prey, help our kin and so on. These drives appear to our mind as attachment and aversion.

Manifestations of attachment include sexual desire, hunger and the need for security. Manifestations of aversion include fighting, fleeing and avoiding painful and dangerous situations. All these mental reactions have evolved because they gave our ancestors a selective advantage. They are, or were, essential for preservation of the individual and procreation of its genes.

We humans can to some extent distance ourselves from these drives. We can examine them and if necessary rebel against them. From the Buddhist point of view this is especially significant when these instinctive drives become pathological and turn into harmful 'innate delusions', giving rise to mental states such as anger, hatred, sadism, jealousy, greed, miserliness, sexual abuse and so on.

4.2 Intellectually formed delusions

|

| 'as dangerous in a man as rabies in a dog' |

4.2.1 Viruses of the mind

'Mind viruses' (otherwise known as malignant memes and memeplexes) are contagious delusions, which harness the three poisons of the mind to spread like infectious diseases. Jihadism is such a meme, which is 'as dangerous in a man as rabies in a dog', to quote Winston Churchill.

The study of memes, memeplexes and their mechanisms of infection is known as memetics.

The Quran is the meme that provides the justification for beheadings, rapes, mutilations, genocides etc carried out by the Islamic State and their co-religionists.

The Quran demonstrates the self-reference and circularity typical of many memes. The Quran says it's the word of God, and believers know what it says is true because it's God's word! Therefore its incitement to rape, murder, extort and pillage the kuffars must be obeyed without question.

Of course any logical analysis shows the Quran's truth claims to be a hoax, but logical analysis, and indeed any forms of rationalism, are strongly discouraged by Jihadists. In addition, divinely sanctioned rape, murder, extortion and pillage provide a very useful excuse for the criminal activities so evident among Jihadists in kuffar (non-Muslim) countries. No wonder Jihadism is spreading so rapidly in jails: it's a criminals' charter. Just as typhus was the Victorian 'jail fever', jihadism is the modern prison epidemic.

4.2.2 Scientism and materialism.

Materialism is the belief that matter is the only reality in life and everything else, such as mind, feelings, emotions, beauty etc are just the by-products of the brain's physical and chemical activity, with no independent existence of their own. Once their material basis is gone, mind and consciousness just disappear without trace. Needless to say, materialism denies the validity of all religions and spiritual paths, not just Buddhism.

The debilitating effects of materialism don't just affect religions; they despiritualise all in their path, degrading art and encouraging brutalism.

Philosopher Roger Scruton believes that all great art has a 'spiritual' dimension, even if it is not overtly religious. It is this transcendence of the mundane that we recognise as 'beauty'.

Although materialism undermines the basis of all religions, nevertheless, materialism is of special interest to Buddhists, because Buddhism is the only religion that has a sufficiently strong philosophical basis to confront it. Buddhism can argue rationally against materialism, whereas less intellectually grounded religions can only bury their heads in the sand and ignore it, while their congregations decline and their institutions get taken over by small cliques of extremists.

As the Abrahamic religions have failed to tackle materialism, and instead are degenerating into antiscience, idiocy and bigotry, Buddhism could become the only object of refuge for intelligent spiritual seekers wanting to escape the bleak and barren consequences of materialism.

5. Liberation of the Mind

|

| Get me out of here! |

5.1 Stepping outside the system

The concept of liberation from delusions by 'stepping outside the system', or ‘jumping outside the loop’ occurs repeatedly in different contexts within Buddhist philosophy and practice. The archetypical example is, of course, the Buddha himself, who escaped from the endless loop of Samsara (cyclic existence) when he became enlightened.

In a philosophical and religious context, this stepping outside a system is known as transcendence, but there are also more mundane examples that serve as useful analogies.

5.2 Cultivating qualitative states of mind

Both formal meditational practice and a more informal approach using art may be employed to produce beneficial mental states.

5.2.1 Meditation

Many meditations consist of a two-stage process, analytical meditation followed by placement meditation. For example, in meditation on compassion a procedural mental process is used to generate a qualitative state of mind. The qualitative mental feeling of compassion is what is known in Western philosophy as a 'quale' (singular of qualia). It is an internal subjective state generated from the observation or recollection of external events. The objective of the placement stage is to familiarise and 'mix' the root mind with this beneficial state.

The ultimate and most profound meditation is that of tantric bliss and emptiness.

5.2.2 Art and aesthetics

The experience of art often fulfills yearnings similar to the inspiration offered by religion. One more profound relationship between art and religion has historically been how it acts as a vehicle for expressing religious teachings. The worldly appreciation of cultural beauty is infused with a sincere belief that the aesthetic of religious art is not for its own sake, but to transmit ultimate truths...

Scruton believes that all great art has a 'spiritual' dimension, even if it is not overtly religious. It is this transcendence of the mundane that we recognise as 'beauty.

In Buddhist terminology we would say that true art, even when it reflects samsara (the realms of chaos, addiction, squalor and suffering), shows that there is a path out, and often acts as signposts along the path.

In addition, as explained here, 'when somebody regards an image of a Buddha, because the object is by nature outside of samsara we accumulate non-contaminated karma, even if we don’t see it as anything more than a pretty piece of art. Venerable Tharchin explains that “the location of mind is at the object of cognition,” so if our observed object is outside of samsara, then the part of our mind that observes that object literally goes outside of samsara. Cognizing the object is a mental action, creating karma. This is why Geshe-la began the International Temple’s Project. Busloads full of children and tourists come, each one leaves with non-contaminated karmic imprints on their mind. These imprints later ripen in the form of these people finding a path out of samsara, or even being directly reborn outside of the prison of samsara.'

5.2.2.1 Symbolism

The three main ways of accessing intuitive levels of the mind are symbolism, visualisation and ritual. Symbolism may be used on its own, or in combination with visualisation and ritual.

The concept of symbolism has two aspects - Representational Symbolism and Evocative Symbolism, though sometimes a representational symbol can, with familiarity, become an evocative symbol.

Evocative symbols are interpreted by and affect the more subtle levels of the mind. Evocative symbolism is associated with art, architecture and poetry, especially where there is a spiritual aspect. Examples of evocative symbolism in the visual arts are icons, thangkas, mandalas, stained glass windows and statues of holy beings.

Evocative symbolism often doesn't use direct representation, reference or explicit analogy. As the symbolist Mallarme said "Don't paint the thing itself, paint the effect that it produces".

"Japanese aesthetic ideals are most heavily influenced by Japanese Buddhism. In the Buddhist tradition, all things are considered as either evolving from or dissolving into nothingness. This "nothingness" is not empty space. It is rather a space of potentiality.[5] If the seas represent potential then each thing is like a wave arising from it and returning to it. There are no permanent waves. There are no perfect waves. At no point is a wave complete, even at its peak. Nature is seen as a dynamic whole that is to be admired and appreciated. This appreciation of nature has been fundamental to many Japanese aesthetic ideals, "arts," and other cultural elements. In this respect, the notion of "art" (or its conceptual equivalent) is also quite different from Western traditions".

Subject Index